1. Devised back in 1980s

The earliest known ransomware was devised by Joseph Popp. Popp wrote the “AIDS” Trojan (aka PC Cyborg) in 1989. It claimed the user’s license for a software program had expired, encrypted file names on the hard drive, and then required the user to pay US$189 to the “PC Cyborg Corporation” in order to unlock the system. It encrypted the file names using symmetric cryptography. Once experts had a chance to analyze the malware code and encrypted tables, it became simple to reverse the process (these days encrypting ransomware uses asymmetric cryptography) and track down the author.

Ten unstructured facts about #ransomware

Tweet

2. It encrypts data or blocks entire systems; asks for ransom in both cases

Essentially there are two types of ransomware – blockers and encryptors.

Encryptors are the Trojans that encrypt every kind of data that may be of value to the user without their knowledge. This can include personal photos, archives, documents, databases, etc. Blockers are Trojans, too. Some of the more prominent blockers are based on other Trojans, such as Reveton based on ZeuS banking malware. This kind of malware just blocks the infected systems and demands payment.

3. Exists for multiple platforms

Ransomware became extremely popular in the second half of 2000. Initially, most of the victims were Windows-based PC users. In time, ransomware for other platforms emerged, including iOS, Mac OS X, and Android.

4. Paying may be in vain

As with real-world extortionists, there is absolutely no guarantee that they will adhere to their part of the “deal”. Even if a victim chooses to pay, it doesn’t mean they will get access to their files. The best course of action here is to do everything possible to prevent infection.

5. Distributed as other kinds of malware

There are many ways ransomware is distributed, but most often it is delivered via spam, or acts as computer worms, inciting users to launch or download the malicious payload using generic social engineering techniques.

The original Cryptolocker, for instance, had been distributed via Gameover ZeuS botnet, and was destroyed by law enforcement agencies during the famous Operation Tovar targeting that botnet’s infrastructure. Unsurprisingly, cybercriminals join forces for mutual benefits. During the operation a database of private keys used by Cryptolocker was recovered, after which an online service was established in order to help victims recover their encrypted files using those keys. For free, of course.

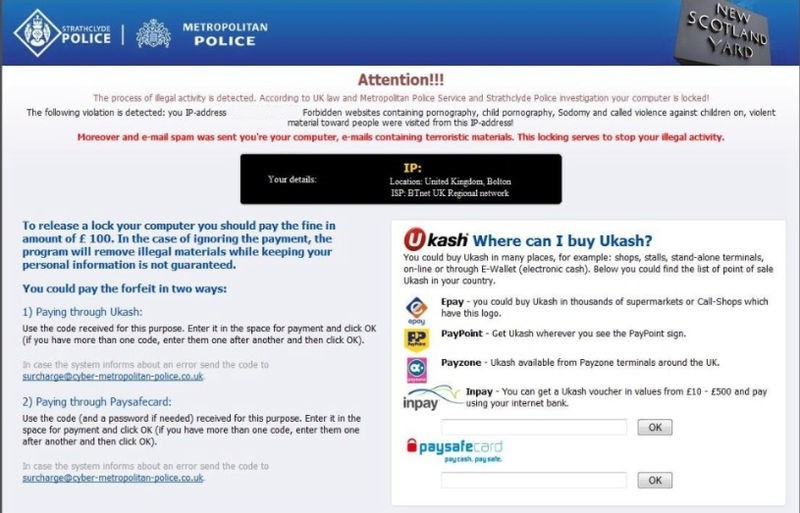

6. Displays fake message purported to be from law enforcement organizations

Ransomware commonly attempts to spook the users displaying fake messages purportedly from law enforcement agencies, and accusing them of various violations. There is a case described in Wikipedia, where a person turned himself over to police after receiving a fake FBI message accusing him of possessing child pornography, which he had. He was arrested and held without bond. In this instance, one evil unearthed another.

#Ransomware generates a good profit, even if only 1% of its victims choose to pay

Tweet

7. Sophistication grows

Encryptors have increasingly used sophisticated RSA encryption schemes, with ever-increasing key-sizes. By mid-2006 the dreaded Gpcode.AG used 660-bit RSA public key. In two years its new variant already used 1024-bit key, which was next to impossible to break without a concerted distributed effort. Cryptolocker already used a 2048-bit RSA key pair.

8. Procures uncertain millions

Ransomware “procures” millions for its operators, although exact data is scant at best. The estimates of both amounts paid, and the number of victims who chose to pay, are varied.

ZDNet monitored four Bitcoin addresses associated with CryptoLocker owners, and found the movement of almost 42 thousand BTC (equivalent to about US$27 million) over three months in late 2013. Surveys of CryptoLockers victims showed various results – 0.4% to 41% reported paying a ransom. After the Gameover ZeuS takedown, it was reported that roughly 1.3% of its victims chose to pay. That’s not very much, but still good enough for the criminals to keep trying. New and “better” ransomware comes in droves, and some – like Onion Trojan – is quite unique, original, and extremely dangerous.

9. Charges big

The extortionists demand a payment of 300+ USD or Euro via an anonymous pre-paid cash voucher (MoneyPak, Ukash) or an equivalent amount in Bitcoin within a limited timeframe. If the payment doesn’t arrive in time, the public key gets deleted and encrypted file recovery becomes impossible. Companies receive much larger demands.

10. Back data up to beat it

Preventing ransomware from attacking systems requires basically the same approach as with every other malware – keep vulnerable software up-to-date, block or limit any kind of unauthorized access to the data, etc. But there’s a twist: an offline backup is an insurance policy against this threat, provided that encrypting malware hasn’t already slipped in. But even if it has, there is a window of opportunity to get rid of it after the data is retrieved from the backup.

Encrypting files takes time and needs processing power. There is none of the latter in the offline backup storage, so encryption doesn’t occur and there is the possibility of recovering data or identifying the malicious files and processes to remove them.

#tips

#tips

Tips

Tips