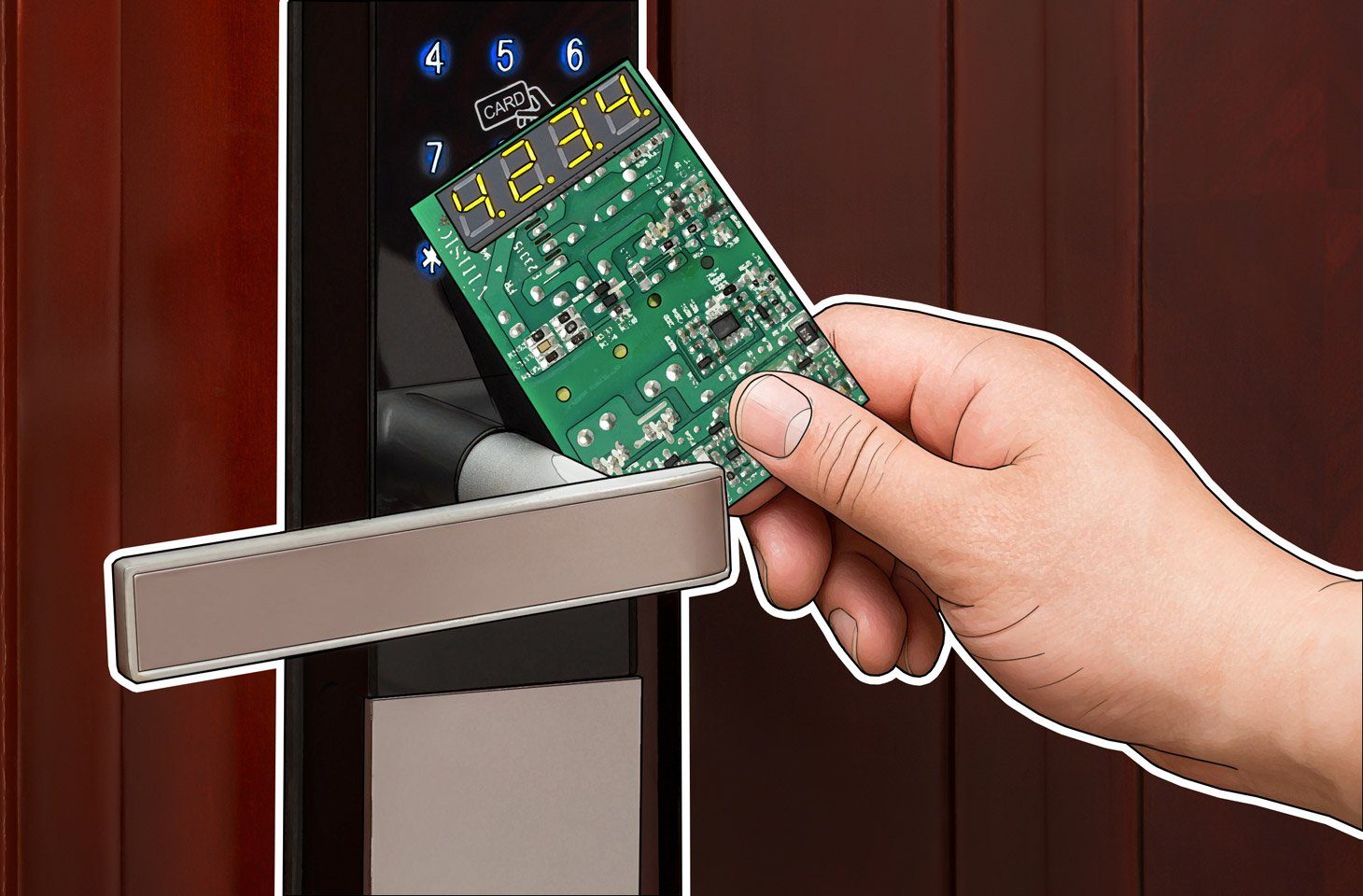

What do movie characters typically do when there is a door with an electronic lock on their way? They call a hacker, of course. The hacker connects some sort of contraption to the lock. During the next several seconds, the device picks every possible combination and shows it on its (obligatory, bright) segment display. Voilà! The door is open.

At Black Hat 2017, Colin O’Flynn, who presented a report on breaking electronic door locks, made a joke about the hardest challenge for characters in such a film — coming up with a brilliant line for that moment when the door opens.

To what extent is this consistent with reality? If we’re talking about industrial-grade electronic locks, not at all. However, quite a few electronic locks for private houses have appeared on the market lately, and those locks are not doing great.

O’Flynn acquired two samples of home electronic locks and examined them. He found the first model vulnerable to so-called Evil Maid attacks. This means that a malefactor needs to gain physical access to the lock’s internal parts just once. Once inside, they can easily add their own code, which will allow them to open the door whenever they want.

No special skills are required: Step-by-step instructions on how to add the code are located right inside the battery compartment. There is no need to enter any existing user code or master code during the process.

The other model did not have this flaw; however, it proved vulnerable to an attack from the outside. The outer part of the lock contains a module with a touch-screen for entering a PIN code. Turns out, this module can be easily extracted (the researcher did it with a table knife), revealing a neatly placed connector.

After studying how the external and internal parts of the lock interact, O’Flynn was able to create a device that looks just like the ones in films about hackers. Naturally, it had a segment display, a bright one indeed. The device itself had to be connected to the aforementioned connector (the electronic part of the lock does not check what exactly is connected) to brute-force the code.

Of course, the lock manufacturer anticipated brute-force attacks. After more than three incorrect tries, the lock’s alarm activates. Nevertheless, O’Flynn found that applying a certain voltage to the external connector’s contacts short-circuits the internal electronics, rebooting the system and resetting the failed-attempts counter.

As a result, the device O’Flynn created can check approximately 120 codes per minute. Going through all of the possible four-digit PIN combinations for the lock takes about 85 minutes. In most cases, that means it takes a half-hour to an hour to pick the lock — a far cry from the several seconds it takes in films, but as for the rest, it’s pretty much like the movies.

Moreover, O’Flynn found a way to pick the lock’s master code. Master codes are longer, and having six digits instead of four extends the brute-force attack time to nearly a week. Yet another bug in the electronic lock firmware speeds up the process quite a bit, however: When you enter the first four of six numbers of the master code, the system either shows an error message or waits for the other two numbers to be entered, thus confirming that the first four digits are correct.

This method requires the same 85 minutes (tops) to brute-force the first four numbers of the master code and one minute more for finding the last two numbers. After that, it is possible to reset the access code to your own. It is also possible to delete the existing codes, leaving the owner with the choice of breaking the door or getting his own hacker.

O’Flynn has already contacted the lock manufacturer, who, he said, was very responsive. The vulnerabilities (and some other security problems) will be fixed as soon as possible.

In general, however, the results of the research send a clear message: Electronic locks for home users still fall short on security. Mechanical locks are undeniably flawed as well. However, that topic has been studied much more thoroughly, at least, and subject-matter experts can reveal which models are better in terms of security. Which electronic locks are really secure and which are not remains to be seen.

black hat

black hat

Tips

Tips